If customers are satisfied and loyal, shouldn’t customer lifetime value increase?

Imagine that you manage a customer service center for a mobile service provider. Four different customers call in, their two-year contracts about to expire. Their service was fine; none plan to switch providers. However, they are thinking of buying new phones and changing plans. How should your customer service agents treat them? This may seem like a simple question, but the relationship between the customer and an organization is anything but simple. Customer satisfaction, loyalty, and lifetime value depend on a complex relationship between customer characteristics and customer service representative characteristics. In this article, I’ll review some of the latest academic research and explain how they view this delicate interplay.

Customer Satisfaction and Lifetime Value: Not Directly Related

Traditionally, researchers and practitioners believed that customer satisfaction and customer loyalty were both positively related to customer lifetime value (CLV). If customers are satisfied and loyal, shouldn’t CLV increase? Recent research suggests that increasing CLV may be more complex. Qi, Zhou, Chen, and Qu (2012) surveyed mobile data service users in the United States and China. They found that being a satisfied customer had no effect on how much money customers spent or how long they remained with their mobile service provider. Interestingly, the more satisfied customers were more loyal to their mobile service provider. Thus, it appears that while customer satisfaction itself does not directly affect CLV, satisfied customers are more likely to be loyal customers, and loyal customers lead to increased CLV. (See Figure 2.6.)

While it is important to understand how customer satisfaction and customer loyalty affect CLV, for customer service managers, it may be more important to understand how to increase customer satisfaction. As mentioned, both customers and customer service representatives have unique characteristics that they bring to every interaction. An understanding of how those characteristics affect customer satisfaction is therefore important.

Customer Characteristics: Widely Varying

According to Puccinelli and colleagues (2009), customers have different goals. First, some customers have a relational orientation (i.e., they want to establish a relationship with organizational members), while others have a task orientation (i.e., they just want to get the information or product and get out). Second, customers have previous positive or negative experiences that affect how they interact with the organization. Third, they have different levels of involvement. Some customers thoroughly research the product and are very involved in their purchase, while others go into the interaction with very little preparation. Fourth, customers often have either positive or negative opinions toward the organization even before being involved in the transaction. Finally, customers have feelings that might affect how they interact with an organization.

Personality is another relevant factor. Homburg, Muller, and Klarmann (2011) suggest that customers and customer service representatives have specific and preferred communication styles. Some customers have an interaction orientation, which means they enjoy a sociable, personal approach. In contrast, customers with a task orientation prefer to focus on the task at hand, rather than engaging in extraneous personal conversation.

These customer characteristics are clearly beyond the control of a customer service representative. However, the way that customer service representatives react and interact with the customers is key. A one-size-fits-all approach is not only ineffective, but might actually decrease CLV through decreased customer satisfaction. With that in mind, we now turn our attention to an area that is controllable: customer service representative characteristics.

Customer Service Representative Characteristics: Under Your Control

Research shows that customers are more likely to buy a product from an attractive salesperson than an unattractive salesperson (DeShields, Kara & Kaynak, 1996). Being friendly (e.g., smiling) also increases a customer’s purchase intention and their willingness to return (Oliver, 1993; Tsai, 2001). Helpfulness is also very important—more important than physical attractiveness or friendliness (Keh, Ren, Hill & Li, 2013). While this may seem intuitive, it does provide a framework for successful customer interactions.

Perhaps most important is how representatives communicate with customers. Homburg et al. (2011) identified two ways in which service representatives might interact with the customer: relational versus functional. A customer service representative who uses a relational orientation is more likely to build a personal relationship with a customer. This person will be helpful and friendly, often engaging the customer in small talk as they establish a personal relationship. On the other hand, a customer service representative who uses a functional orientation employs a set of behaviors that is designed to get the job done. They may still be helpful and friendly, but they do not engage in relationship-building behaviors.Putting It All Together

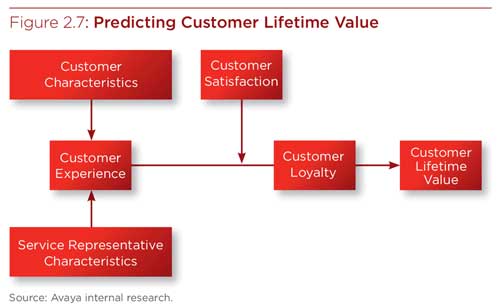

Figure 2.7 provides a comprehensive model for the relationship between customer experience and CLV. According to Homburg et al. (2011), customer characteristics and service representative characteristics are both related to customer experience. A positive customer experience will increase customer loyalty, while a negative customer experience will decrease loyalty. However, customer satisfaction, which depends on more than just their experience (e.g., product performance), affects this relationship. High customer satisfaction facilitates more loyalty, while low customer satisfaction attenuates the relationship between customer experience and customer loyalty.

Let’s revisit the earlier scenario (mobile consumers seeking customer service). There are four possible outcomes:

Jamie does a lot of research online to find the phone and the service plan that best fit his lifestyle. When Jamie calls the service center, he has a task orientation. He knows the phone and the service plan that he wants and he just wants to get it done. The representative who answers the call senses that Jamie is task oriented and establishes a functional orientation. Customer loyalty increases, boosting CLV.

Evelyn also knows what she wants when she calls the service center to order her phone. However, this time the customer service representative adopts a relational orientation and tries to establish a more personal relationship. Evelyn, who just wants to buy the new phone and change her service (task orientation), is annoyed by the small talk. She mistrusts the rep, suspecting him of trying to sell her a service she does not need. Evelyn decides to go with another carrier. CLV goes down.

Charlie does not really know much about phones. He has a very basic phone with a limited plan. He wants the sales representative to educate him about different phone features and engage him socially, too. Charlie has an interaction orientation. The sales rep senses Charlie’s orientation and adopts a relational orientation. Both parties are on the same page. Having enjoyed his purchase experience, Charlie’s loyalty increases, causing CLV to rise.

Melanie is also unsure of her phone needs when she calls the service center. The customer service representative establishes a functional orientation and tries to help Melanie without establishing a personal connection. Melanie, who is very social, was hoping for the same (interaction orientation). Although the sales representative is very efficient in helping Melanie buy a phone, Melanie felt he was rude, which decreases her loyalty (she decides to go with another carrier) and her CLV.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Good customer service can increase CLV, while poor customer service can decrease CLV. However, the effect is indirect and heavily influenced by other parts of the customer experience. There is no template that can be applied to these interactions. Instead, customer service representatives should be trained to recognize customers’ needs early in the interaction so that they can tailor their communication style appropriately. If a customer is interested in establishing a personal relationship, the representative should be able to become more friendly and engaging. If the customer is purely task oriented, the service representative should focus on being businesslike and helpful.

Training can be accomplished in two ways. First, representatives can be screened for emotional intelligence. There are many personality measures that can measure the degree to which people can pick up on interpersonal cues to help adjust their behavior. Second, representatives can be trained to better understand a customer’s preferred communication style and adapt accordingly.

Organizations are starting to employ the latter method. BASF, a global chemical company, has developed six different customer interaction models (CIMs). For example, a supplier purely interested in the transaction needs a low-intensity interaction. On the other hand, customized solutions require a higher-intensity interaction. The customer service representatives identify the appropriate CIM for each interaction. Indeed, multiple scripts might be one way to enable customer service representatives to better communicate with customers. Regardless of the approach, customer service managers should understand that the relationships between customers and customer service representatives are dynamic and require more than a one-size-fits-all approach.